The Kashmir Question is one of the world’s oldest unresolved issues, one that is of global significance to humanity today. The issue not only impacts on relations between India and Pakistan, the two immediate protagonists, but it also directly affects peace and stability far beyond South Asia.

The end of the British Empire in South Asia led to the break-up of the Indian Subcontinent; the latter was divided into two dominions: India (represented by the National Congress with its Hindu majority), and Pakistan (represented by the Muslim League, with a Muslim majority). At the same time, the Princely States (also known as the Native States which were never part of formal British India) were given the right to accede to one or other of the two newly formed independent countries.

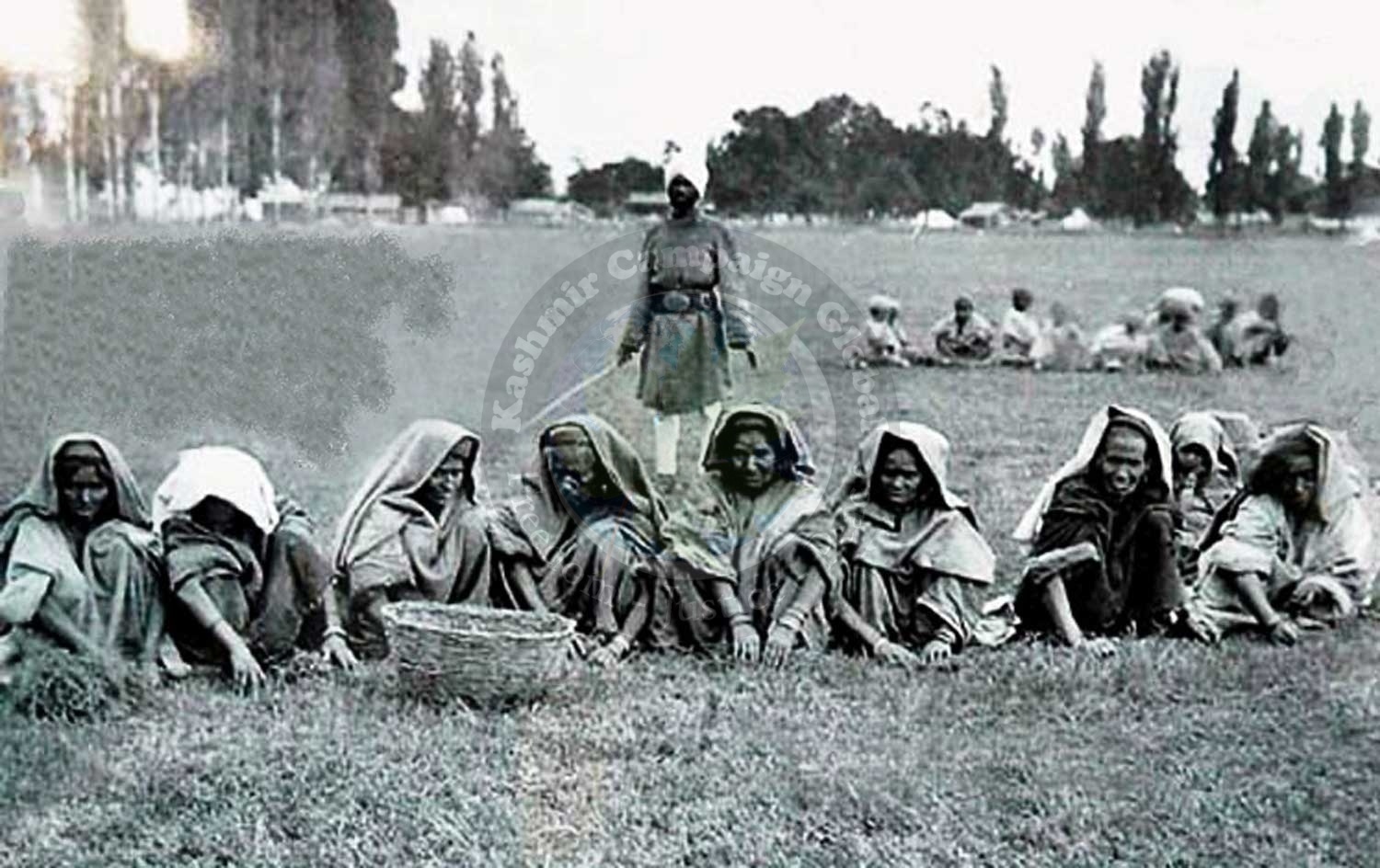

A Dogra soldier watching over Muslim Kashmiri women with a rod in hand during “beggaer” or forced labour

The Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir, the second largest of all the Princely States, was always predominantly Muslim and thus, following Partition, the people expressed a desire to accede to Pakistan. However, the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir at the time, Hari Singh, who happened to be a descendant of the Hindu Dogra dynasty, and whose own claim to hereditary rulership of the region remains controversial*, wanted to remain independent and therefore formed a standstill agreement with both India and Pakistan; this was duly ratified by Pakistan but objected to by India who refused to sign it.

*(Hari Singh’s ancestor, Raja Gulab Singh, was the founder of the Dogra dynasty who infamously obtained the territory from the British East India Company in 1846 for an annual sum of ‘protection’ money)

On 27th October 1947, India flew its armed troops to Srinagar, claiming it had done so based on the signing of the Instrument of Accession (IoA) by the Maharaja the previous day (26th October) under the pretext of curbing a popular uprising by the people of Jammu and Kashmir. The validity of this IoA has since been challenged numerous times by historians and scholars.

In January 1948, India brought the Kashmir Question to the United Nations after realising that it would not be able to quell the growing resistance by the people of Jammu and Kashmir, a resistance supported by volunteers from the newly-created Pakistan who had already helped liberate a third of the territory (which it called ‘Azad Kashmir’, ‘azad’ meaning ‘free’).

On 21st April 1948, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) passed Resolution 47, developed on common grounds between India, Pakistan and the international community, that provided a solution to the Kashmir Question. The Resolution focused on creating a ceasefire line, the withdrawal and progressive reduction of military forces by both Pakistan and India respectively, and a free and impartial plebiscite under the control of an Indian-appointed administrator nominated by the UN Secretary-General.

Two further UN Resolutions were adopted by the Security Council, on 13th August 1948 and 5th January 1949 respectively. These Resolutions jointly embodied concrete terms of settlement relating to all issues as recommended by the newly-formed United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) in close consultation with the two countries. Both Resolutions were formally signed by India and Pakistan and constituted an international binding agreement. Moreover, the United Nations Military Observer Group (UNMOGIP) was created in 1949 to monitor the ceasefire line. The group had a limited mandate to monitor the ceasefire and report on any violations directly to the UN Secretary-General. The progress towards a peaceful solution came to a halt when India again obfuscated the agreed-to international process by refusing to accept the reduction (and thus eventual withdrawal) of her forces in accordance with the terms – and spirit – of that agreement.

Between 1950 and 1957, various mediators acting through the established UN agreement process, including US President Harry S Truman, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee, Canada’s General Andrew McNaughton, and Australia’s Sir Owen Dixon, made intense efforts to secure a peaceful solution to the growing imbroglio through a phased demilitarisation effort in order to allow for the holding of a free plebiscite.

During the Cold War, India’s new ally, the Soviet Union, used its United Nations Security Council right of veto to further prevent any progress towards a peaceful solution and unfreeze the forced stalemate. Since then, wars have sadly been fought between India and Pakistan over Kashmir (in 1947, 1965 and 1999)